Djémia Trari (6 mins read)

In recent years, the landscape of French far-right politics has undergone a significant transformation, particularly in its approach to gender issues. This shift, epitomized by Marine Le Pen’s leadership of the National Rally (formerly National Front), presents a fascinating paradox that challenges traditional perceptions of far-right parties as exclusively male-dominated entities.

From Männerparteien to Femonationalism

Historically, far-right parties have been viewed as “Männerparteien” — parties of men, by men, and for men. These organizations typically promote sexist and machist discourses, appealing primarily to a white male audience. Their narratives often centered on the idea that white men were losing their societal position due to people of color and a few “traitor” white women, fueling a rhetoric of protecting “privilege” and “civilization” through hyper-masculine ideologies.

Interestingly, while women have not traditionally been the target audience for these groups, they have become integral to the far-right’s narrative of superiority. These portrayals are often paradoxical and instrumentalized for racist purposes, a phenomenon Kathleen Blee refers to as “scavenger ideology.” In her seminal work, Blee categorized the ways women are depicted in racist groups into four distinct narratives:

- Goddess/Victim: White women are portrayed as racial victims needing protection from non-white men.

- Race Traitor: Women who associate with non-white men are labeled as traitors to their race, undermining “racial purity.”

- Wife and Mother: This narrative emphasizes women’s roles in transmitting bloodlines, traditions, and languages, portraying their procreation as an act of activism for racial welfare.

- Female Activists: A more modern portrayal aimed at attracting women to join far-right movements, often depicting them as “comrade wives” or “racial combatants.”

If these categories remain relevant in order to understand traditional women narratives in racist groups,far-right parties have seen the number of female leaders rise in recent years. It is therefore interesting to explore what arguments remain from the « Männerpartei ».

The literature has now embraced a broader definition of gender by including the concept of intersectionality, which can help to have a deeper understanding of different women experiences and aim.

« Intersectionality« is a term introduced by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989 that present women or minority’s experiences and identity « as a result of the intersection between different social categories and constructs » rather than cumulative. Indeed, having an understanding that there is not only one type of feminism can help to grasp the evolution of gender narratives and ideologies in far-right parties.

Marine Le Pen strategy and narratives within the Front National and now Rassemblement National are a good illustration of the paradoxes of populist parties gender stances. Indeed, the far-right has shifted towards “femonationalist” discourses when it comes to gender.

Coined by Sara R. Farris, “Femonationalism” describes the intersection of nationalist ideologies with selective feminist ideas, often driven by xenophobic motivations. Femonationalist discourse focuses on women’s rights primarily when discussing immigration and multiculturalism, often ignoring domestic gender inequalities. It involves instrumentalizion of women’s rights and feminist language to legitimize anti-immigration and Islamophobic policies. It portrays immigrant cultures, particularly Islam, as inherently sexist and oppressive to women, while presenting Western societies as bastions of gender equality. Ultimately, they propose a hegemonic conception of female emancipation by encouraging women to adopt the norms of Western femininity to claim freedom.

Between Feminism and Nativism

Le Pen’s strategy involves a careful balancing act. While softening the party’s image on certain issues, such as abortion rights, she maintains a strong stance against immigration and multiculturalism. The party still employs “nativist” rhetoric: protecting french women’s rights against the perceived threat of immigrant cultures, particularly those from Muslim countries.

Nativism is an ideology, governmental policy, or political stance that prioritizes the interests and well-being of native-born or long-established residents of a given country over those of immigrants, typically by advocating or enacting restrictions on immigration. Those who hold this view tend to reject or avoid the term nativist and instead identify themselves as “patriots,” “nationalists,” or “populists.”

This approach aligns with what Kathleen Blee described as the “Goddess/Victim” portrayal of women in racist groups.

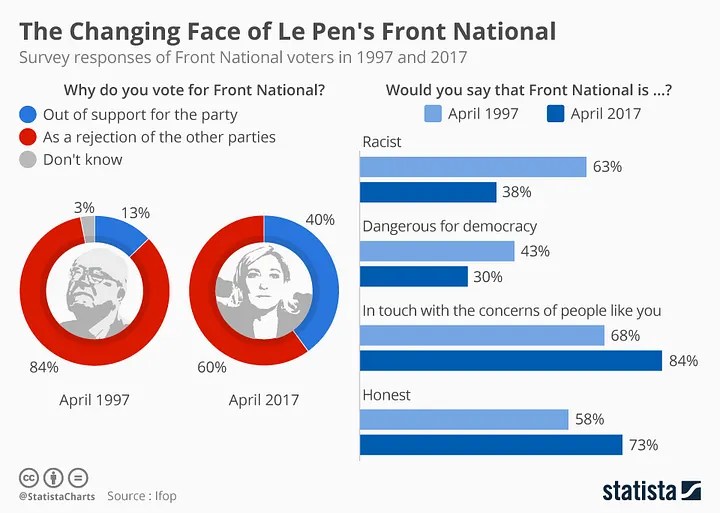

Le Pen has managed to modernize this narrative, framing it within a context of secular, republican french values. The chart below shows how Marine’s attempts to clean up and modernize the party’s image has potentially changed the perception of the party’s value and managed to attract a much wider spectrum of French society.

Closing the Radical Right Gender Gap

Le Pen has positioned herself as a modern, emancipated woman and a “quasi-feminist,” marking a stark departure from her father’s era, which championed traditional gender roles. This shift has led to a significant closing of the Radical Right Gender Gap (RRGG) in France. In the 2012 presidential election, Marine Le Pen achieved almost equal support among female and male voters, a trend that continued in subsequent elections. By 2024, the National Rally attracted nearly equal support from women and men in the European parliamentary elections.

The feminization of the French far-right intensified during the 2010s, with the formation of several far-right women’s groups and increased female participation in movements like “Manif pour tous”, a queerphobic far right movement. This trend has been accompanied by a softening of the party’s image and rhetoric, making it more palatable to a broader range of voters, including women and young people.

An Unchanged Core Ideology

Critics argue that this “feminism” is superficial and manipulative. Feminist groups contend that the National Rally’s approach to women’s issues is a political ploy rather than a genuine ideological shift. The party’s stance on gender equality remains controversial, often viewed as a strategic tool to attract voters while maintaining its core bigoted values.

The paradox lies in the fact that while Le Pen has successfully attracted more female voters and presented a more modern image, the fundamental ideology of the party remains largely unchanged. The use of republican, secularist, and feminist references appears to be a veneer masking a still-strong nativism. The values of the party still remain as xenophobic, racist, antisemitic, sexist and dangerous for democracy as when Marine’s father was in charge.

A challenge to the traditional understanding of far-right ideologies

This evolution reflects a broader trend in European far-right politics, where parties are increasingly using gender equality rhetoric as a tool to legitimize anti-immigration discourses.

The case of Marine Le Pen and the National Rally illustrates the complex interplay between gender, politics, and nationalism in contemporary far-right movements. It demonstrates how these parties are adapting their strategies to appeal to a wider electorate, particularly women, while maintaining their core ideological positions.

As France approaches future elections, including the 2027 presidential race, the impact of this gender-focused strategy on the far-right’s electoral success remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that the evolution of gender dynamics in French far-right politics represents a significant shift in the political landscape, one that challenges traditional understandings of far-right discourse and their appeal to different demographic groups.

Sources:

Scrinzi, Francesca. “Racialisation of Sexism: The Case of the National Front in France.” Gender and Politics in the European Union, 2017.

Blee, Kathleen. Inside Organized Racism: Women in Right-Wing Movements. University of California Press, 2002.

Alduy, Cécile. “Marine Le Pen’s Political Communication: A New Image for the National Front.” Stanford University, 2015.

Sciences Po Research. “Closing the Radical Right Gender Gap: Female Voter Support for Marine Le Pen.” Political Science Review, 2018.

Samie, A.. “nativism.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 19, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/nativism-politics.

Growth Think Tank. “The Feminization of the French Far-Right: Women’s Groups and Their Impact.” European Political Science Journal, 2020.

Farris, Sara R. “Femonationalism: The Gendered Politics of Anti-Immigration Movements in Europe.” Social Politics, 2017.

France 24. “Marine Le Pen’s Approach to Women’s Rights: A Political Strategy?” 2021.